Bishop Christopher Coyne writes:

At times I have wondered why even after his resurrection Christ still bore the wounds of the Cross. His is a resurrected and glorified body, one no longer bound to this physical realm. Could not then, the perfection of His new creation be perfected in appearance as well?

Two thoughts: the first goes back to the words of the prophet Isaiah in 53:5, “by his wounds we are healed.” Perhaps it is Christ’s “wounded-ness” that is the perfection of creation because it was by His perfect sacrifice on the Cross that we were healed of the wound of sin and division that kept us from God.

The second thought is more personal. It is a reminder that in my own death I will bear all the wounds of this present life, those that are a part of my physical humanity and those that I bear on my soul as a result of sin. All that is of me now will be a part of me then. Hopefully, I will still be found worthy of a merciful judgement.

In response a friend recalls a legend that the Devil appeared to St Teresa of Avila in the form of Christ himself. But she immediately called him out. He asked her how she could tell it wasn’t the Lord and she replied, “You have no wounds.”

I keep coming back to the petition in the Anima Christi prayer: ‘Within your wounds hide me.” I’m perpetually baffled by it, but I keep coming back to it again and again. It feels important. If I could understand it, I could crawl in to the mystery, if I could really truly desire to be hidden in those wounds… what would that be like?

The closest I can come is desiring to wrap myself up in the shroud like a security blanket and being surprised to find that in my imagination of being in the tomb I found the blood on the shroud a comforting presence rather than being disgusted by it.

I wrote about this here: We’re in the Tomb with Jesus:

I’m wrapped in the shroud like a child wrapped in a best beloved blanket, Sophie with her Flower Blanket worn to rags, Ben with his White Blanket draped over him during Mass, carefully arranged on his pillow at night so he can press his face against it.

The shroud smells like perfumed oil, the smell rubs off on my skin. There is blood on it. It’s not scary, smelly, or sticky. It’s sweet like wine. The very best wine.

So the tomb, the shroud, they speak deeply to me. But the wounds themselves still somehow baffle me. I pray the prayer fervently, wanting to mean it, wanting to know what it means: within your wounds hide me.

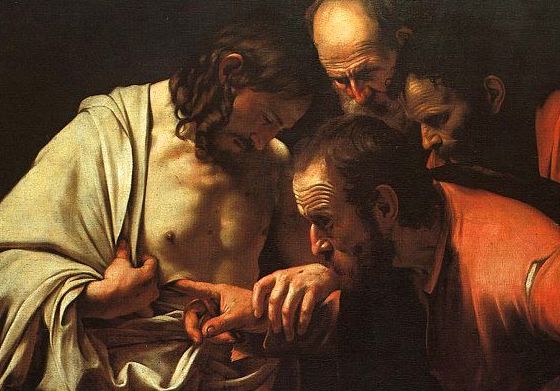

A friend says she connects it to St Thomas, which makes sense. He actually probes those wounds, sticks his finger in to the cavities. And there’s a healing moment there… by his wounds you are healed indeed. Thomas’ doubt is resolved by the wounds themselves. He then becomes the very first to call Jesus My Lord and my God. The first to declare definitively Jesus’ godhood in unambiguous language.

The reality of Jesus’ wounds dispels all doubt. Within them we have no room to doubt his love for us. See, here, this is how much I love you. In Heaven he still, continually, presents those wounds to his Father, his sacrifice is always here and now, not only then, on Calvary, two thousand years ago. His wounds are still with him. Not healed, not obliterated.

As long as there is a human to suffer we need those wounds. They say: See, I am suffering with you. I am suffering for you. You are not alone. Come, hide your wounds within my wounds. We will bleed together and my blood will fill your wounds. My blood will heal you.

The Psalmist says, “you are my hiding place, O Lord.”

My rock, my fortress, my place of refuge.

Place. Jesus is a person but also, somehow Jesus is a place. Just as when a child is gestating in his mother’s womb, Mother is a Place. Small children know this too. Mother is a safe place, a refuge, a hiding place. And there is something about the idea of hiding within Jesus’ wounds that evokes something of that imagery: to be entirely within another person, shielded and protected by their body– yes, that is a very maternal image.

What strikes me in Caravaggio’s painting of the incredulity of Thomas is Jesus’ tenderness. The so gentle look he turns to Thomas. He isn’t angry, isn’t impatient. He’s all love, all compassion, all patience. He gently holds Thomas’ wrist and guides his hand, that probing finger. As a mother carefully guides her child’s hand when he’s still learning how to use a tool: here, right here, that’s right, just like that.

Perhaps I don’t have to understand. Maybe asking is enough. Maybe he’s already holding my wrist, guiding my finger.