“Odysseus was melting into tears;

his cheeks were wet with weeping, as a woman

weeps, as she falls to wrap her arms around

her husband, fallen fighting for his home

and children. She is watching as he gasps

and dies. She shrieks, a clear high wail, collapsing

upon his corpse. The men are right behind.

They hit her shoulders with their spears and lead her

to slavery, hard labor, and a life

of pain. Her face is marked with her despair.

In that same desperate way, Odysseus

was crying. No one noticed that his eyes

were wet with tears, except Alcinous,

who sat right next to him and heard his sobs.”The Odyssey, trans. Emily Wilson, Book 8 lines 21-34

I’ve been listening to Emily Wilson’s lovely translation of The Odyssey. Wilson’s goal, in her translator’s notes is stated as “a certain level of simplicity, often using fairly ordinary, straightforward, and readable English. . . . recognizable as an epic poem, but it is one that avoids trumpeting its own status with bright, noisy linguistic fireworks, in order to invite a more thoughtful consideration of what the narrative means, and the ways it matters.”

And I believe her translation of the poem achieves that goal. I’m noticing all sorts of things I’ve never noticed before. (Of course the last time I read or listened to The Odyssey was probably two decades ago.)

Among other things, I’m noticing the high frequency of weeping in the poem. Boy does Odysseus cry. Almost, it seems, at the drop of a hat. He is always sobbing. This is not what a modern reader expects from a great warrior. Aren’t they supposed to be stoic and brave and hold their emotions in? And he’s not the only one, other Greek warriors cry too. Clearly Homer and his audience have a very different attitude towards men crying than we do.

* * *

I’ve also been talking about inter-generational trauma with my friend Kate, who says:

“My friend’s therapist says that difficulty achieving/maintaining empathy is a PTSD symptom. When she told me this, soooooo many things about family patterns of abuse suddenly made more sense to me. I never used to understand why people repeat the same actions that hurt them so badly, but if the part of you that can imagine what other people are feeling and experiencing is busted…”

And since I’ve been listening to the Odyssey, I started thinking about the traumas of war, about warriors coming home and acting out in violent ways. Long before shell shock or PTSD were understood, how did men handle— or not handle— the traumas of war? Surely wars were not less traumatic then. Well. . . maybe bronze era warfare was a little less traumatic than modern mechanized warfare. . . but I’d be wiling to bet that even then men were still traumatized. War is war, is violent and terrible in any age.

* * *

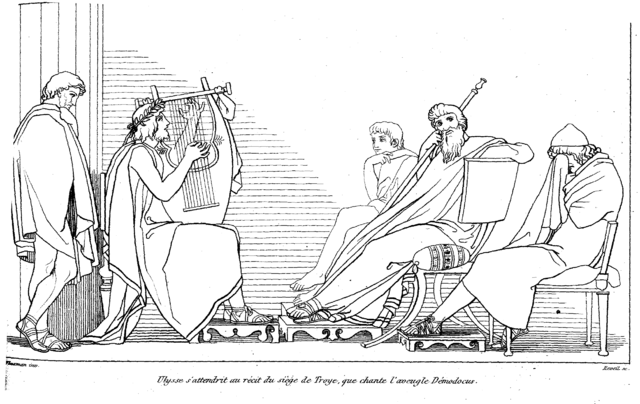

And in a flash I thought about Odysseus sitting in the home of King Alkinoos of the Phaekians, throwing his cloak over his head and sobbing out his grief as he listens to a song about the Trojan War. And then the king, in a wonderful display of empathy for his guest, notices his grief and suggests that they all go out and engage in sports: boxing, wrestling, high-jumping, and sprinting. And then more poetry and more crying and finally Odysseus tells his own story of his adventures thus far, the deaths of his men at the hands of the Cyclops and the Lystrigonians, etc. And they all drink wine.

There is so much empathy displayed in these episodes in Book 8 of the Odyssey. Not least in the heroic simile used to describe the weeping Odysseus: he’s compared to a wife who has lost her husband in battle and is being taken away as a slave. Homer calls his listeners to empathy not only for the traumatized warrior, Odysseus, but also for the women, the victims of the worst brutalities of war. I think there’s something going on here.

* * *

And that sends me diving back to my college days and my favorite English professor at UD, Dr. Louise Cowan, speaking about poetry as therapy. When she was younger she’d had eye surgery and while she was recovering had to wear a bandage and lived in total darkness for some time. She said poetry saved her life, people came to read to her and talk to her, but there were long hours of dark solitude. It was then that she recited poetry from memory. I wish I had a copy of her essay on the same subject because it was so so beautiful. Alas, it is lost to me unless at some point someone republishes it. (Ooh! Dom found it via web archive!)

But as I thought back to Dr Cowan I realized that her thesis about poetry as therapy seems to apply very specifically to PTSD and the epic poem. In the Odyssey as the hero listens to his battles recreated as poetry and as he struggles to organize his own narrative as he describes the horrors he has endured on his long voyage home, Homer is showing, that the singing of war poems and the telling of war stories is a sort of therapy and re-training in empathy. In warrior cultures like the Greek and the Viking and the Anglo-Saxon, when warriors returned home from battle, they sang songs and told stories of the battles they had just fought as well as of other battles of long ago.

* * *

I’m no expert in modern psychotherapy, but I’m more and more intrigued by the idea that this singing of war stories could be a ritualistic way of processing the grief and the trauma of war and is strangely analogous to contemporary treatment of post traumatic stress. Poetry allows the traumatized warrior to relive his trauma in a controlled narrative, to give it form and structure and meaning and context, and to share that traumatic experience with others. It also gives him a chance to cry and to publicly grieve his lost comrades.

And then, in the Greek context at least, the ritual funeral games also give warriors a secondary outlet a way to work off those powerful emotions that the poems and stories stir up in a physical way, with strenuous competition and even controlled violence— as boxing and wrestling contain and direct the need to hitting or push or hurt. So that rather than taking out his violent impulses in a domestic context on a helpless victim in his family or household, games redirect it into a safer venue as he competes with his friends, his brothers, his fellow soldiers and sailors.

In Homer then war epics are not just entertainment or the glorification of war, but a societal safety valve. They are actively therapeutic, a methodology transmitted by oral tradition. A sort of group therapy in which warriors process the traumas of war so that they can re-enter civilized life without the kinds of post-traumatic stress that we see in modern soldiers erupting in disorderly and disruptive and destructive ways. Of course we don’t have any real documentary evidence for how well this group therapy worked, but I have a hunch it did have real cultural value.

* * *

In the Telemachiad, the first part of the Odyssey, which is itself the paradigmatic homecoming narrative, we are shown examples of men of war like Nestor and Menelaus who seem to have reintegrated into society. And those like Agamemnon who fail to reintegrate. Then the story of the Odyssey invites the listener to enter into the narrative more deeply, to witness in detail the re-entry process for Odysseus himself. To say it is not without violence is an understatement. In fact it turns into a pitched battle as he kills the suitors, he kills the maidservants/slave girls who consorted with the suitors. If it were not for the divine intervention of Athene, there might have outright war with the suitors’ families. Yet Odysseus’ violence is also controlled and methodical and arguably not unjustified.

Additionally, the Odyssey narrative suggests there is need need for a further ritual of cleansing, the dead seer Tiresias tells Odysseus that he will have to make a journey away from the sea with an oar over his shoulder until he comes to a place so far from the sea that the locals take his oar for a winnowing fan, not knowing what an oar is. This pilgrimage seems to be a ritual of atonement for the deaths of all of his men on the journey home and likely also has a healing function. Going away from the sea, the location of his trauma, would not be easy for a man who lives on an island. And yet it seems like it might be vital for his reintegration.

* * *

The Odyssey presents several cultural strategies that seem to parallel modern treatments for PTSD.

Cognitive processing therapy helps people make sense of bad memories, by re-examining what happened in a more factual way to get a more realistic perspective on the trauma. As Odysseus re-orders his memories and takes responsibility for his failures, you can see something like this at work:

“Now something prompted you to ask about

my own sad story. I will tell you, though

the memory increases my despair.

Where shall I start? Where can I end? The gods

have given me so much to cry about.”The Odyssey Book 9, 12-16, Emily Wilson trans.

Odysseus at first casts about, trying to put his experiences into a kind of order. He shrinks from the task of facing those memories which increase his despair. And at first he blames the gods for all his grief. Yet as he spins his tale, he also faces his own responsibility in the deaths of his men and it seems to me finds a balance in recognizing what is his fault and what was beyond his control.

Prolonged exposure therapy, helps traumatized patients face and control their fears by exposing them to the traumatic memories of their experiences in the context of a safe environment using mental imagery, writing, or visits to places or people that remind them of their trauma. As Odysseus hears the stories of the war and tells the stories of his adventures he faces the traumatic events in a culturally acceptable format which must give a kind of safety and security. In fact he begins his narrative by praising the poet who has just been singing and describing the context of the feast, a relaxed, ritualized environment:

“My lord Alcinous, great king,

it is a splendid thing to hear a poet

as talented as this. His voice is godlike.

I think that there can be no greater pleasure

than when the whole community enjoys

a banquet, as we sit inside the house,

and listen to the singer, and the tables

are heaped with bread and meat; the wine boy ladles

drink from the bowl and pours it into cups.10

To me this seems ideal, a thing of beauty.”The Odyssey Book 9, 2-11, Emily Wilson trans.

He reminds himself of the beauty of a well-told poem, of the pleasure of hearing a story well told, and of the comforts of the banqueting hall where there are food and wine and company. This is ideal, a thing of beauty. This feasting hall, he reminds himself, is a safe space for revisiting his traumatic memories.

And, thinking about the use of breathing and relaxation techniques in treating trauma, I’m curious about whether the physical discipline of singing and storytelling, which require the singer or storyteller to moderate his breathing, to conform his voice to the rhythm of poetry, is doesn’t function as a kind of stress reducer.

Like I said, I’m no expert in psychotherapy and I’d love to hear from what people who know more about the subject have to say, but to me it seems that there are many strong parallels. While the discipline of psychology is new, it seems to me that it springs up at about the same time that the poetic tradition has eschewed epic war poetry in favor of Romantic idealism which fades into modernist disillusionment and despair. It makes sense that there was something which fulfilled that role before the advent of psychotherapy. Religion is one obvious candidate— and I’m sure it does play a role— but I’d love to recover the idea of poetry as a not-so-primitive kind of therapy. One that may still serve us well today.

* * *

Your story has both grace and wisdom in it.

You sounded like a skillful poet, telling

the sufferings of all the Greeks, including 370

what you endured yourself. But come now, tell me

if you saw any spirits of your friends,

who went with you to Troy and undertook

the grief and pain of war. The night is long;

it is not time to sleep yet. Tell me more

amazing deeds! I would keep listening

until bright daybreak, if you kept on telling

the dangers you have passed.”The Odyssey Book 11, 368-78, Emily Wilson trans.

Odysseus, tiring, comes to a stopping point in his narrative. But King Alcinous presses him to continue with his story, praising his story telling ability. Odysseus, he says, tells his story as well as a skillful poet and there is grace and wisdom in it. And I think this act of shaping the raw material of his experiences into entertainment for strangers shows that he has in some sense mastered his trauma. He has been able to order his memories into a story, to order it rightly, to find insight and meaning in what he has gone through. The artistry of the story shows that Odysseus, grieved as he is by his losses, has achieved a level of self-mastery over his memories and achieved a meaningful degree of integration.

* * *

My friend Kate suggests that: “Emotional processing and release is one of the original functions of narrative, I think. Think of Aristotle’s mimesis and catharsis–the need for the narrative to be similar enough for the audience to enter into, but distant enough that they can purge their emotional responses as the characters’ story reaches resolution.”

Over the years I’ve struggled to understand Aristotle’s Poetics. When I was younger and first encountered it I don’t think I really had the life experience to be able to fully grasp what trauma is and thus didn’t really have a complete understanding of why emotions would need to be “purged”. Intellectually I understood the idea of mimesis, imitation, and I sort of grasped the idea of catharsis via pity and fear, but I have had a hard time fitting those ancient categories into my modern world. But maybe this notion of trauma and therapy will map onto what it is that is happening in catharsis: the purging of emotions? What does it mean for an emotion to be purged? Is it that it is confronted, allowed to have a certain power on the imagination, and then dismissed, having done its work?

So this is what I’m pondering: for catharsis read emotional integration. For pity read empathy. For fear read traumatic emotional response.

A work of art helps the reader/viewer in a therapeutic fashion to achieve emotional integration by means of a narrative that is close enough to the traumatic experience for people in the audience to enter into the story and relate emotionally, but distant enough for the movement of the characters through their own story arcs toward resolution allows the viewer to be able to disengage when the story is over. The experience of confronting emotion and then dismissing it is a sort of desensitization. And the experience of pity means that poetic narrative helps to reawaken empathy which is deadened by trauma.

I think it’s time for me to go back and re-read the Poetics. I’m still trying to work through this idea.

* * *

Contemporary poet Amorak Huey takes up this theme of epic storytelling in his poem We Were All Odysseus in Those Days:

“He’ll rarely talk

about the war. If asked

he’ll tell you instead

his favorite story:

Odysseus escaping

from the Cyclops

with a bad pun & good wine

& a sharp stick.

It’s about buying time

& making do, he’ll say.”

The soldier of his poem becomes a literature teacher and rather than discussing his war experiences directly, telling about the death of his friends, he narrates the story of Odysseus. And yet this is clearly not merely redirection. Rather, the story of Odysseus gives the soldier a way to reframe his own experiences, to contextualize them. It becomes his way of confronting the trauma of war in a ritualistic way:

“It’s about doing what it takes

to get home, & you see

he has been talking

about the war all along.”

As the poem’s title suggests, he takes on the persona of Odysseus. And it finishes with a rather chilling conclusion:

“We all want the same thing

from this world:

Call me nobody. Let me live.”

* * *

And I cannot skip over the Anglo-Saxon analogy in Beowulf. After Beowulf has defeated Grendel a poet composes a song about Beowulf’s feats and also sings about other great heroes of the past:

“Meanwhile a thane

of the king’s household, a carrier of tales,

a traditional singer deeply schooled

in the lore of the past, linked a new theme

to a strict meter. The man started

to recite with skill, rehearsing Beowulf’s

triumphs and feats in well-fashioned lines,

entwining his words.

He told what he’d heard

repeated in songs about Sigemund’s exploits,

all of those many feats and marvels,

the struggles and wanderings of Wael’s son,

things unknown to anyone

except to Fitela, feuds and foul doings

confided by uncle to nephew when he felt

the urge to speak of them: always they had been

partners in the fight, friends in need.

They killed giants, their conquering swords

had brought them down.”Beowulf, Seamus Heaney trans.

* * *

One of my professors at the University of Dallas, Dr Curtsinger, who taught me about novel writing from the inside out, went to college on the GI bill after the war. He fell in love with Moby Dick and became a literature professor and a novelist. I suspect that for him Moby Dick served something of the same function: a narrative that gave deeper meaning to his life, and taught him the craft of reframing and retelling his own traumas, not directly speaking about the war as one telling war stories, but as a different kind of art to make sense of chaos and death and a world more full of weeping than we can understand.

* * *

“So sang the famous bard. Odysseus

with his strong hands picked up his heavy cloak

of purple, and he covered up his face.

He was ashamed to let them see him cry.

Each time the singer paused, Odysseus

wiped tears, drew down the cloak and poured a splash

of wine out of his goblet, for the gods.90

But each time, the Phaeacian nobles urged

the bard to sing again—they loved his songs.

So he would start again; Odysseus

would moan and hide his head beneath his cloak.

Only Alcinous could see his tears,

since he was sitting next to him, and heard

his sobbing. So he quickly spoke.”The Odyssey Book 8, lines 84-97, Emily Wilson trans.

* * *

Edited to add: I just found this essay while I was looking for an image to illustrate this post. I figured I was hardly the first person to tackle this theme. This reading is slightly different than mine in the details it notes and its account of the workings of poetic therapy, but harmonizes with it well. The Therapy of Odysseus

In modern times, with tens of thousands of veterans returning from our ten-year wars involving multiple deployments, we have reason to pay particular attention to the way in which Odysseus recuperates from his harrowing experiences in war and wandering. He does this through tears and tales: tears that are prompted by emotionally reliving those harrowing experiences, and tales that put them into a narrative shared with sympathetic listeners. By telling them to others, he is relieved of their burden.

Granted that soldiers who have suffered a 10-year deployment and a 10-year detainment cannot in a mere three days be healed (such is fictional compression), but we can discern the steps that facilitate recovery from combat trauma in one of the first works of western literature.

And, near the end of the epic, when he is finally in bed with his wife Penelope, and Athena has prolonged the night to give them time to catch up, Homer is careful to inform us that Odysseus told her “everything” and even provides a synopsis of all the episodes he had related to the Phaeacians. The final homecoming is only complete when all the traumatic experiences are put into a narrative and shared with a sympathetic listener.

Melanie, this is GREAT! Thank you for writing this… I need to pick up the Poetics again too.

Thank you. It was one of those things that just had to be written.

Also, I edited the end of my blog post to include a link to another essay that tackles the same theme. I just found it while I was looking for an image to illustrate this post. I figured I was hardly the first person to tackle this theme. This reading is slightly different than mine in the details it notes and its account of the workings of poetic therapy, but harmonizes with it well. The Therapy of Odysseus

What a marvelous, fascinating reflection and analysis! Thank you so much for writing and sharing this. I am reminded of how long it has been since I read Homer–and even longer since I read the Odyssey in particular.

A brilliant contemporary book I read on this theme is “On Killing,” by Dave Grossman, an army psychiatrist. He examines the psychological effects that killing in war has on the men who kill and how they deal with (or fail to deal with) the trauma. Grossman drew an interesting distinction between how US servicemen dealt with war in WWII versus Vietnam.

In WWII men generally served in the same unit with the same other men for their entire service–and the expectation was that they would be in the war for the duration. That created a bond of common experience, made them a kind of community. Then, at war’s end, they would generally go home on the most up-to-date transportation available: ships. This meant they would be together for perhaps a week, which gave them time as a community to think and talk and get ready for the return home. The journey home served as an informal, unintended period for processing the trauma of war.

In Vietnam, men would be rotated through various units and were expected to stay for the duration of their particular tour, not the entire war. Moreover, when they finished they would now fly home and be back in civilian life much more quickly. This made men more isolated and gave them less time to process all they had been through. Grossman argues this made PTSD and unresolved problems more likely. (I am not sure precisely how things have been in more recent wars, but I suspect closer to the Vietnam than WWII model, alas…)

I know of a book that directly talks about Homer, specifically the Iliad, and how it offers insights into contemporary war experiences. It is called “Achilles in Vietnam” by Jonathan Shay. I have not read it but would like to, and it might interest you as well.

Thank you, John. Those books both look interesting. I’m fascinated by the idea of the journey home itself being a form of therapeutic healing. It would make sense that soldiers not having the transition time nor the fellowship of their friends would suffer more extreme trauma.