We’ve been reading Men, Microscopes and Living Things, which is a sort of history of biology for children. On the whole I really like the book. It’s well written and engaging. But the chapters on medieval herbalists and medieval bestiaries both raised my eyebrows a bit and sparked some interesting discussions as I questioned the book’s bias and raised several objections to its assumptions.

While it’s true that in the medieval world natural history was not yet highly prized as an intellectual discipline and there were many superstitions about both plants and animals, still, we have a habit of selling the Middle Ages short and perpetuating the myth of the Dark Ages. It’s notable how most children’s books will praise the Greeks and Romans as proto-scientists and gush about their curiosity and the scientific bent of their minds, while excusing their errors, and then blast the medievals for their lack of scientific curiosity, while highlighting their errors and superstitions which aren’t really any more egregious than those of the ancients. There is a distinct post-Enlightenment, anti-Christian bias in many books for kids.

The Herbalists, Superstition, and the Case of Bald’s Eye Salve

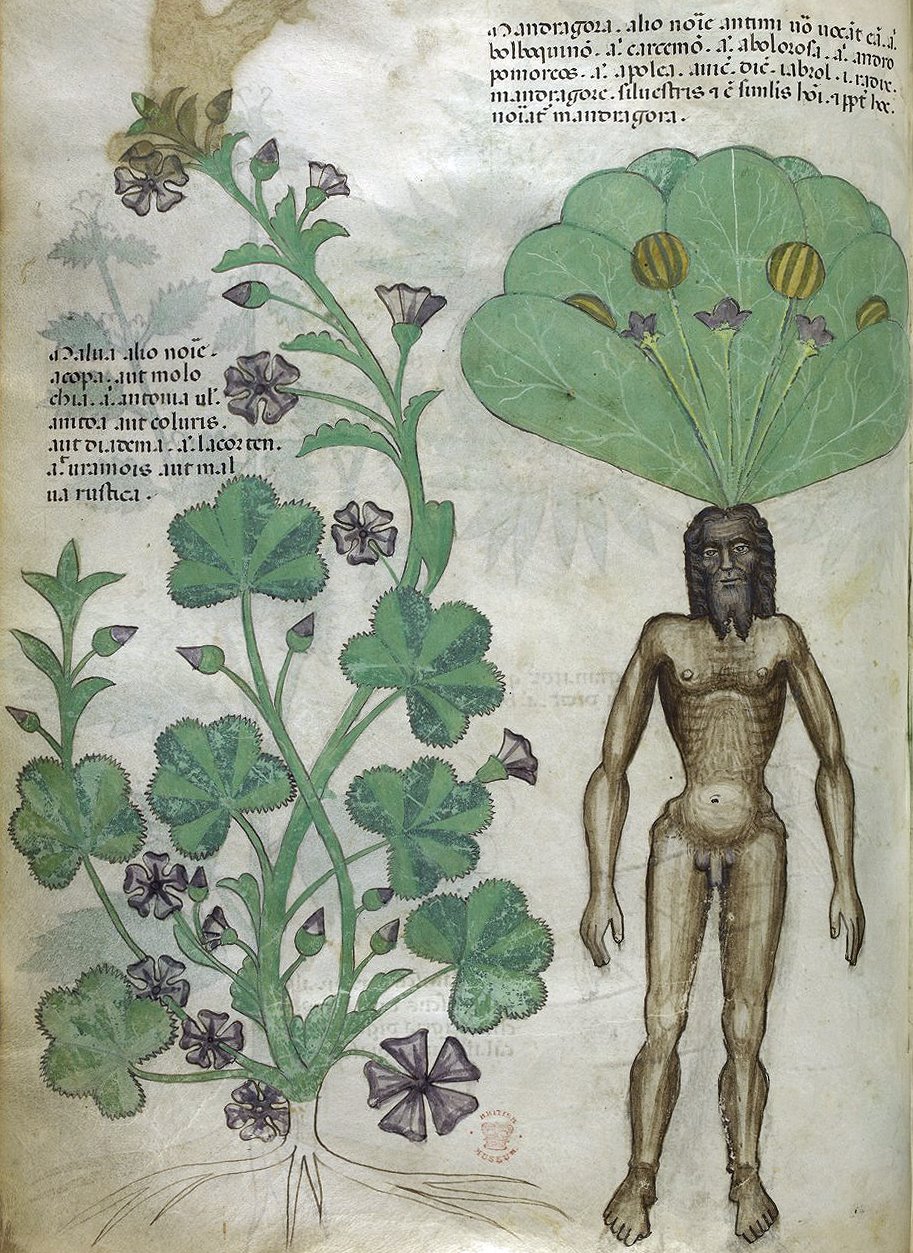

The chapter on the herbalists focuses mostly on superstition. It doesn’t seem to have a deep insight into the way faith shaped the Medieval worldview, only some superficial observations, some of which are rather half-truths. It does say that the herbalists were driven by necessity into a close observation of the plant world, which it said few other medieval thinkers were very interested in. I suppose there’s some support for the argument that a comprehensive system of classification was lacking before Linneus, but that doesn’t mean that the medievals didn’t have their own methods of classification, even if we think they are inferior.

It concludes: “But though gradually men were beginning to put aside the superstitions that had surrounded plants for so long, they had not yet found out much about them. They would have been surprised to learn that all the herbs and roots had not been created ‘for the delight of the health and the comfort and life of the sick,’ but were part of the world in which men and all other living things are joined.” That conclusion isn’t doesn’t make sense, what the author describes is not really a discovery but a shift in worldview, from one that looks primarily at the world as God’s creation, to a pragmatist materialist worldview. But the medieval worldview doesn’t exclude the notion that all living things are joined. That seems like a really clunky attempt to highlight the difference between the two ways of understanding the world.

In any case, recent scientific research has begun to look at the medieval herbals in a new light and reconsider the work done by herbalists. Maybe there was a lot more close observation and experimentation done and less superstition that we previously believed. The Ancient Biotics Project is a collaboration between medievalists and microbiologists at the University of Nottingham. There have been several articles about their research on one recipe in particular called “Bald’s Eye Salve”:

“At a lecture given at the Library of Congress on March 7, 2017, medievalist and biologist Erin Connelly told the story of the experiment with the 1000-year-old recipe known as Bald’s Eyesalve.* She is part of the interdisciplinary Ancientbiotics team which explores the relevance of medieval medicines for modern infections.

She claims that “Recent scholarship may show that there is more methodology to the medicines of medieval practitioners, and further inquiry may show that their medicines were more than just placebos or palliative aids but actual antibiotics being used long before the advent of modern infection control.”

Bald’s Eyesalve

The recipe that sparked the debate is found in a book held by The British Library. Titled Bald’s Leechbook, the book has the ancient Anglo-Saxon recipe written in old English. The ingredients are organic materials accessible to everyone in the locality. It requires garlic and alliums, which could either be onions or leeks. These are mixed with wine and ox gall. The mixture is then put in a brass vessel and let stand for nine nights. After straining and clarifying, it is put in a horn and applied to the eye with a feather.

What seems like a haphazard collection of liquids and herbs was found to be much more. Researchers replicating the recipe found that any omission from the recipe dramatically diminished or eliminated its bactericidal qualities. Similarly, each ingredient on its own had no significant effect on the reduction in bacteria. They found that the nine-night incubation period served to make the mixture self-sterilizing and therefore effective. Likewise, omitting this period made the recipe ineffective.

The tests revealed a method of observation and experimentation that was anything but haphazard. Moreover, this was not a cure-all concoction. Dr. Connelly believes that it seems to have been specifically targeted for what it was made to treat.”

(Did Medieval Medicine Ever Work?)

Read more about the project at the Smithsonian Magazine: Medieval Medical Books Could Hold the Recipe for New Antibiotics .

Beastiaries and Beatrix Potter

The chapter about medieval bestiaries sort of takes them at face value: “Each story has a moral attached to it, and is intended to describe the habits of the animal and also to set forth the teachings of the Church.”

Although it begins does suggest that a primary purpose of the bestiary is the morality tale, it also assumes that medieval readers were unsophisticated and couldn’t tell the difference between real animals and fantastical creatures or fantastical attributes being given to real creatures. Did medieval people truly believe the hedgehog impaled grapes on its spines and took them back to its family or was it a fantasia? Most moderns assume that medieval people never bothered to observe the common hedgehog and maybe that’s true— maybe they were credulous and unobservant— but maybe not. Maybe they just enjoyed fantastical tales much as modern children enjoy Beatrix Potter’s talking animals and the cunning details of the mouse houses in Jill Barklem’s Brambley Hedge.

Sigrid Undset makes a cutting observation about the 19th century’s blindness to the medieval worldview— that blindness continues in some quarters even to this day. “. . . discovered that much that had been scoffed at by the rationalists as medieval childishness, crudity, and the outcome of silly superstition, was in fact nothing but the symbols and emblems of that age. It had simply appeared meaningless to the people of the age of enlightenment in the same way as stenography looks like a meaningless scribble to those who know nothing of shorthand systems.”

Gregory Roper also points out that literary conventions which are understood as conventions in the age in which the works are written might be quite misunderstood and taken literally by readers unfamiliar with the conventions of the genre:

I explain to my students that, as far as medievalists have been able to determine, no real historical person ever acted in the way the fin amours poets repeatedly describe. That is, earlier historians who took fin amours texts as describing what actual eleventh-century humans did in their courts, their gardens, and their bedrooms were, we now know, quite wrong. What a fin amours lyric describes, it would seem, is a set of literary conventions perhaps vaguely resembling reality, but more important, powerfully shaping the possibilities for subject matter, persona, imagery, diction, and more.

I suspect this is the case with the medieval bestiary, which was never intended to be any kind of biology text, but was intended as a text on morality, illustrated with creatures that would intrigue and amuse, to delight and entertain the reader’s fancy. If they seem ridiculous to modern readers, perhaps it is our own preconceptions that make them so. If we could read them as a medieval reader would, maybe they wouldn’t seem quite so diconcerting.