**Spoilers**

Just so you know, I don’t avoid giving away plot points. If you haven’t read the book and don’t like having things ruined, come back later.

“The real story isn’t half as pretty as the one you’ve heard. The real story is, the miller’s daughter with her long golden hair wants to catch a lord, a prince, a rich man’s son, so she goes to the moneylender and borrows for a ring and a necklace and decks herself out for the festival. And she’s beautiful enough, so the lord, the prince, the rich man’s son notices her, and dances with her, and tumbles her in a quiet hayloft when the dancing is over, and afterwards goes home and marries the rich woman his family has picked out for him. Then the miller’s despoiled daughter tells everyone that the moneylender’s in league with the devil, and the village runs him out or maybe even stones him, so at least she gets to keep the jewels for a dowry, and the blacksmith marries her before that firstborn child comes along a little early.”

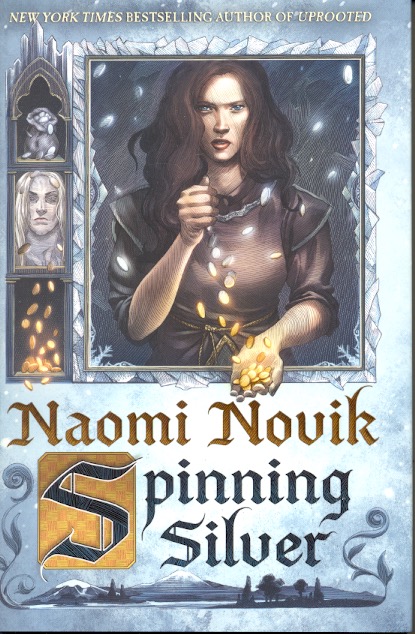

Spinning Silver by Naomi Novik is a fantasy novel that explores the stories behind the stories you thought you already knew. You know, the proverbial “other side of the story”. In short, it’s about questioning the narrative. The story is told in the first person, from multiple first person narrators, three protagonists, and a couple of secondary characters. At times it’s a little confusing; each time the narrator shifts it takes a few lines before you are sure who is telling the story. And perhaps that confusion is deliberate. It certainly seems to be a playful riff on the idea of a subverted, destabilized narrative.

The novel opens with Miryem’s revisionist retelling of the Rumplestiltskin story. Because Miryem is the first speaker and because her storyline often feels dominant, it’s tempting to think of her as the novel’s protagonist. (Perhaps she is and perhaps Irina and Wanda are really secondary characters while Margra and Stepon are tertiary?) Anyway, Miryem’s version of Rumplestiltskin is a demystified inversion of the traditional tale of the miller’s daughter who makes a bad bargain and tries to trick her way out of paying back the debt she owes. To Miryem it is clear that the “real” story is that Rumplestiltskin isn’t a magical gnome who grants wishes but a Jewish moneylender who has been cheated by the miller’s daughter, who was jilted by the son of the lord who had no intention of marrying her. She defaults on her loan, convinces the villagers to drive away the moneylender, and keeps her jewelry as a dowry to marry the blacksmith. The villain in Miryem’s telling is not Ruplestiltskin but the miller’s daughter.

There is no magic in Miryem’s version of the tale. Just human greed and concupiscence and betrayal and folly. To Miryam the original fable exists to scapegoat the Jewish moneylenders and as the daughter of a moneylender she’s having none of it. She puts the moneylender into the role of wronged victim. But soon we find out that while her tale is pure rationalist prose, Miryem actually lives in a world where magic exists, and her village is threatened by the elf-like Staryk lords. And soon she is caught up in a different version of the story than the one she wants to tell, a story that is a cross between Rumplestiltskin and Beauty and the Best. Miryam is kidnapped by the fairy king who heard her boast about turning silver into gold— he takes her literally and expects her to work magic for him. Unexpectedly, in his realm the magic does work and she is able to turn silver to gold.

And yet over time we learn that there are two sides to this story, too. As Miryem gradually collects the fragments of the Staryk king’s story, learning in in all her interactions with them that the Staryk see the world in a very different way, he seems gradually less and less evil. Like Beauty or Psyche, her world gradually shifts as she comes to have some pity for the enemy/ captor /husband. In a nice twist of events it turns out that he is just as wrong in his assumptions about her as she is in her assumptions about him. Rather than an all-knowing, godlike husband he turns out to be critically blind and in his pride and refusal to bend he resembles no one so much as Pride and Prejudice’s Mr Darcy.

Miryem is the sixteen year old daughter of an unsuccessful moneylender in a village so small it’s not even on the map; and no one can even agree on the village’s name. Names, it turns out, are an important element in Spinning Silver just as they are in the original Rumplestiltskin where the miller’s daughter has to guess the gnome’s name to prevent him from taking the firstborn child she so rashly bargained away. Echoing Rumplestiltskin’s fairy gnome, Staryk king refuses to tell Miryem his name. Later she finds out that bestowing names on her Staryk servants gives her power over them. And knowing the name of a fire demon gives the Staryk king power over that demon.

I’m fascinated by the way the novel riffs on the images of silver and gold. Silver is associated with winter and with the Staryk who seem to be spirits of winter. Gold, on the other hand, is associated with sunlight and warmth. When she turns silver into gold Miryem unwittingly is taking heat and sunlight from her own world and trapping them in the fairy realm. She’s effectively spinning an endless winter— making her somewhat like the White Witch in Narnia. Also, when Miryem has a jeweler turn the Staryk silver into a ring, necklace, and crown so that she can sell them to a rich lord for gold— thus proving the Staryk’s misunderstanding to be true and putting her into his power— she is unknowingly handing over a part of their power over winter to the lord’s daughter.

Irinia, the lord’s daughter, had a part-Staryk mother and thus a native affinity for the power over winter inherent in the Staryk silver. The enchantment on that silver from fairyland gives Irina a glamour that turns the heads of all the nobles in the land. She also beguiles the young, unmarried tsar who falls into Irina’s father’s trap, deciding that he must have her. Though curiously what catches the notice of the tsar is not the glamour of the fairy silver, but Irina’s complete indifference to him. He finds her disinterest absolutely irresistible.

Married against her will to the monstrous tsar, Irina uses her power over winter to escape from him night after night, there’s a little echo of Scheherazade whose storytelling prowess saves her from the death sentence (Irina herself references the story). So the story spins around two unconsummated marriages between two hard-hearted, reluctant brides married to kings who can destroy them and whose powers are bent on destroying the world the brides love. To save their beloved kingdom from the ravages of eternal winter, the two wives plot to turn their husbands on each other, to let the fire demon and the winter king fight it out. And yet in the end that solves nothing. The key that unlocks each woman’s fate and ultimately saves the kingdom is learning to care. As their stony hearts melt Irina and Miryem take action in which they put themselves at risk.

It turns out, too, that Irina especially has an untapped talent for leadership and her leadership of the kingdom in time of crisis, her deft management of complex politics, not only wins over her husband but also gains her the approval of her father who from the beginning seemed to see her only as a piece of property to be bargained for power and not as a powerful person in her won right.

Rounding out the trilogy of narrators is Wanda. Although she doesn’t drive the action as much as either Miryem or Irina, she plays a crucial role and without her actions Irina and Miryem would have worked themselves into a deadlock. Wanda is a Cinderella figure whose dead mother’s spirit lives on in a magical silver tree which gives her brother a magical nut that turns out to be very important. She is the oldest daughter whose after the death of her mother is being ground down by her drunk and abusive father. Sold into slavery to pay his debt to the moneylender, Wanda actually welcomes the change and the chance to get away from the marriage her father plans. She strikes a bargain with Miryem that offers her a new path, a way out of her misery. Wanda doesn’t end up married, but she does find what she wants even more than a husband: a family. Freeing her younger brothers from her father’s abusive household, Wanda eventually leads them all to safety and a new home in a magical place between Irina’s world and Miryem’s.

The story is rounded out with the narratives of Wanda’s younger brother, Stepon and Irina’s nurse, Magreta. I loved their perspectives, which reminded me that so often in fairy tales it’s the unexpected and the weak who win the day. Stepon as the youngest son could have been the hero of his own fairytale in his own right. I loved that even though he was a minor character he still had a pivotal role to play and was given a voice. And Magreta. the servant wasn’t just a foil for Irina. She has her own arc, her own revelations, her own struggle and her own kind of magic. Without these two minor voices the novel’s tapestry would have been much less rich and I can’t help feeling that something that I can’t quite put into words yet would have been lost. I probably need to re-read the book at some point to figure out exactly what it is those two characters do. They aren’t as important as Irinia or Miryam or even Wanda, and sometimes their story arcs feel a little thin in comparison. But there again is a key difference between novel and fairytale. A novel is capacious enough to offer a multiplicity of points of view. And perhaps that is the point: there is always another side of the story, always a different point of view to consider. That is what Spinning Silver does best: it overturns fairy tale tropes to show us a very different kind of story.

[…] I wrote further about it: here. […]