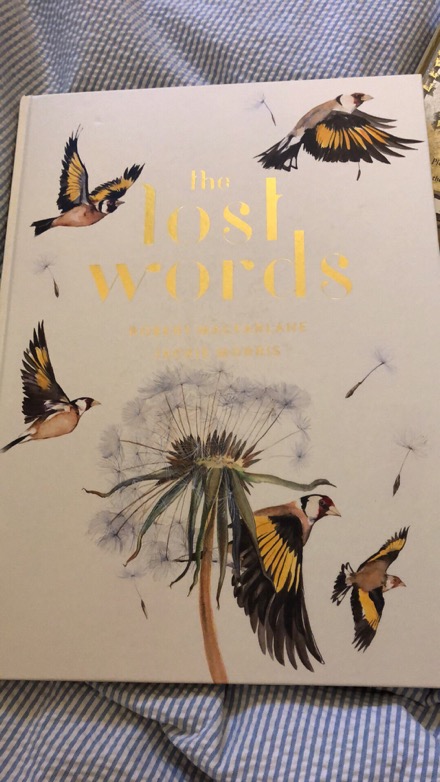

The Lost Words: A Spell Book by Robert Macfarlane, illustrated by Jackie Morris.

The premise of this book is intriguing. Someone noticed that 40 nature words– like fern and heather and kingfisher–were dropped from the Oxford Junior Dictionary in favor of tech words like blog and voicemail. And so a book was born, a book of poems and pictures to highlight some of those “lost” words.

But… this premise was not enough to sell me on this book. I tend to roll my eyes a little bit at the earnestness of “rescuing” words. Especially as these words are not words that are unknown to my kids, who read widely and well. They already know what all these animals and plants are. So why do they need this book? These words have not been lost to us.

But this book isn’t really about learning a handful of words that were dropped from the dictionary. You want this book not as a vocabulary enricher, not because you and your children don’t know the words, but because the book is beautiful, a paradise for nature lovers and art lovers and word lovers.

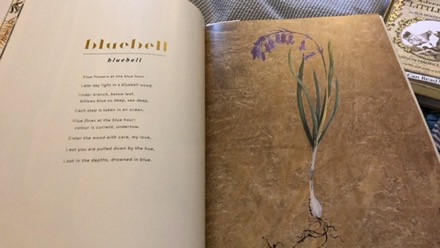

That said, as this is a British book, some of these plants and animals are not native to our New England area. So while the kids do know the words, they relish seeing and learning more about larks and bluebells and heather, which they have only encountered in books. This is the countryside of Swallows and Amazons brought under the magnifying glass: adders and ferns and heather. What a lovely way to learn more about those living things we may never see live and in person, no matter how much we tramp about in our local nature preserves.

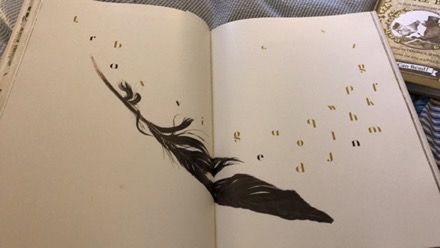

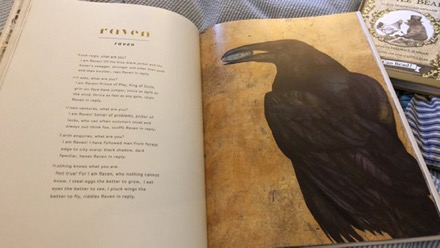

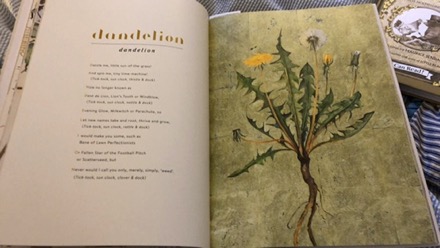

Each of the twenty words gets three two-page spreads. The first spread is a sketch that includes a hint of the plant or animal: an outline, a feather, a line of footprints. Each includes a jumble of letters, most of them gold, but hidden among them the letters of the “lost” word in a contrasting color that matches the plant or animal, blue for bluebells, yellow for dandelions, green for fern. The second spread has a poem and a beautiful drawing of the plant or animal, fit for a guidebook. The plant has all the parts, leaves and flowers and roots. The specimen is framed against a plain gold background. The poem is an acrostic with the first letter of each stanza spelling out the lost word again. The third spread is a nature scene, showing the animal or plant in its habitat. These are fun because they almost all have other plants and animals hidden in the picture, fun to look at for a good long time, reveling in the details.

The pictures are lush watercolors, with rich colors, a feast for the eyes. The poems are deft, surprising, playful. The work of a true wordsmith– and nature lover and word collector. They were delightful to read aloud, the kind of poems you can read over and over again to find new turns of phrase and tricks of meaning.

Take Acorn, a pile of similes “as… as… as…” that doesn’t get the final “so” until the final line, a delightfully increasing anticipation that captures some of the essence of acorn, as seed, a the thing whose deepest nature is that it precedes the final adult plant:

As flake is to blizzard, as

Curve is to sphere, as knot is to net, as

One is to many, as coin is to money, as

bird is to flock, as

Rock is to mountain, as drop is to fountain, as

spring is to river, as glint is to glitter, as

Near is to far, as wind is to weather, as

feather is to flight, as light it to star, as

kindness is to good, so acorn is to wood.

And each poem has its own inner logic, its own mystery and magic. They are true poems, not gimmicks.

Heron is one of my favorites, especially where it captures the stillness of the waiting heron:

“Rock still at weir sill. Stone still at weir sill.

Dead still at weir sill. Still still at weir sill.

Until, eelless at weir sill, heron magically…

unstatues.”

Or where it invites the reader to imagine becoming an otter:

“Run to the riverbank, otter-dreamer, slip

your skin and change your matter, pour

your outer being into otter– and enter

now as otter without falter into water.”

The delightful enjambment, suggesting movement and the repetition of sounds and the playful rhythm of the lines, all are supremely otter-like.

Willow is more mysterious, tree-like, defying easy identification:

“Long you linger, listeners, hard you press your ears against

our bark, but you will never sense our sap, and you will

never speak in leaves, or put down roots into the rot

for we are willow and you are not.”

In Dandelion the poem presents a dizzying array of folk names, playing with the idea of lost words, names forgotten:

“Now no longer known as

Dent-de-Lion, Lion’s Tooth, or Windblow. . .

Evening Glow, Milkwtich, or Parachite, so

Let new names take and root, thrive and grow,”

Then the poet playfully suggests a list of new possible coinages: “Bane of Lawn Perfectionists / Or Fallen Star of the Football Pitch / or Scatterseed…”

Either the pictures or the poems alone would be worth the price. Both together, is an intoxicating combination. Really, you need this book.