On Friday I took the kids to our homeschooling group’s annual Lenten retreat. The theme of this year’s retreat was The Seven Sorrows of Mary. A young priest, Fr. Anthony Cusak, (himself a homeschool graduate) gave a meditation for the mothers that was just beautiful. As he spoke of the Flight into Egypt he referenced a painting at the MFA. I knew I needed to go look up the painting and also that I needed to go look up art to go with all the sorrows and to post them here with some of what I remember from his talk and some of my own thoughts and reflections. So here is the fourth of a planned series of seven posts: First: The Prophecy of Simeon, second: Flight into Egypt, third: The Loss of the Child Jesus in the Temple, fourth: Meeting Jesus on the Way of the Cross

So they took Jesus; and carrying the cross by himself, he went out to what is called The Place of the Skull, which in Hebrew is called Golgotha. There they crucified him, and with him two others, one on either side, with Jesus between them.

Meanwhile, standing near the cross of Jesus were his mother, and his mother’s sister, Mary the wife of Clopas, and Mary Magdalene. When Jesus saw his mother and the disciple whom he loved standing beside her, he said to his mother, “Woman, here is your son.” Then he said to the disciple, “Here is your mother.” And from that hour the disciple took her into his own home.

John 19: 16-18, 23-27

Jesus speaks from the cross seven times, one of these times is to address his mother directly. How must her heart have broken to hear his dear voice addressing her in such pain. When Jesus commits the Blessed Virgin to the care of John the Beloved he is of course providing for her. It has been his duty as the only son to care for his widowed mother, now he entrusts her to John. It would be strange if the God who has always had a special concern for widows and orphans did not make a point to arrange for her welfare. But when Jesus gives Mary to John he is doing something more than merely arranging for someone to see to her welfare. He is also telling Mary that her time of watching over him as a mother is passing away. Now she will have a new mission, a new role of motherhood: to watch over John and through him the whole Church. She is my mother now and yours. Our Lady, our Mother.

How must those words have cut her to the heart? For her son is truly going from her and though he will be resurrected, his resurrection is the beginning of something new and different.

In Juan Sanchez’s painting we see an example of what is a whole sub-genre of crucifixion images: Jesus on the cross with Mary on one side and John on the other. I love these pictures that isolate this moment, emphasizing it by removing all other figures. Here are no crowds, no soldiers, no adoring saints, only the Mother and the beloved disciple, as if they and Jesus were the only people in the world.

Mary’s eyes are cast down. Is it modesty, or grief, or is she looking at something. It almost looks as if she’ gazing at her hand. Has she caught a drop of the blood that is spilling copiously from his wounds? Is she contemplating the mystery of that life-giving blood? Is she contemplating the Eucharist? It is hard to tell if that is what the artist intends, but I think it might be. John also looks down, his hands clasped against his cheek in such a tender gesture remind me somehow that he leaned that cheek against Jesus’ breast just the night before at the Last Supper. I think a tear is rolling down John’s cheek.

But one of my favorite details in this painting is the gorgeous golden filigree that surrounds the Virgin and St John, the beautiful fruit-bearing vine, a reminder that the cross is the Tree of Life, that from Christ’s death springs the Eucharist. I am the Vine and you are the branches. Remain in me. I think, also, that I spy a small church underneath the cross. Is Christ’s blood, dripping down, giving life to the Church?

At the Cross her station keeping,

stood the mournful Mother weeping,

close to her Son to the last.Through her heart, His sorrow sharing,

all His bitter anguish bearing,

now at length the sword has passed.

In van der Weyden’s painting a kneeling Mary embraces the cross while John reaches out to support her. Her face is pressed against the wood right under Jesus’ feet, his blood drips down towards her mouth, again a gesture towards the Eucharist. Her face is the very picture of grief. She clings to the cross, holds it as if afraid she will be dragged away. It is her last farewell to her dying son, or her terrible agony at his passing.

O how sad and sore distressed

was that Mother, highly blest,

of the sole-begotten One.Christ above in torment hangs,

she beneath beholds the pangs

of her dying glorious Son.

In Fra Angelico’s crucifixion Mary has swooned away, completely overcome with grief. In the top half of the painting the soldiers and crowd look up at the crucified Christ, or at each other, or out at the viewer, or stare forward stoically. In the bottom half of the picture the four saints are all focused on Mary, bending over the mother who seems close to joining her son in death. Here again is the gesture from John, the hands clasped and pressed against his cheek. Two of the women hold Mary up and the third– Mary Magdalene?– reaches down. In the golden sky angels reach out to catch his blood in chalices.

Can the human heart refrain

from partaking in her pain,

in that Mother’s pain untold?

James Tissot’s series on the life of Christ is masterful and when it comes to the crucifixion, it’s hard to know which paintings to choose. There are many I love, but I think these two are my favorites that show Mary at the crucifixion. In the first, Mary stands quite close as they drive the first nail into Jesus’ hand. His head thrown back, legs pulled up, his agony is palpable. But Mary and the other women do not turn away. One woman standing behind Mary holds her hands up in front of her face, though she seems to be peeking through her fingers. But Mary looks steadily at her son. Is she remembering the first time she held his tiny infant hands in hers in the stable long ago? Those dear, dear hands pierced through with nails!

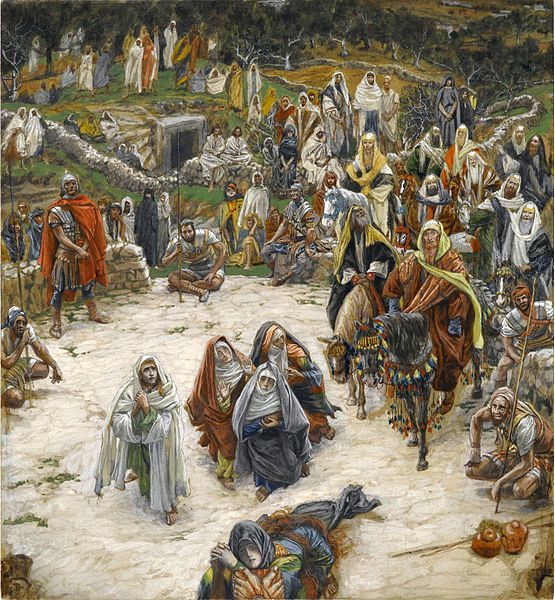

This is one of my favorite paintings ever. A view from the cross itself, Jesus looking down at the crowd. Closest to the foot of the cross is Mary Magdalene, but just behind her in the focal center of the painting is Mary with two other women behind her and St John on her right side. Mary looks steadily at Jesus, at us. Here she does not seem overcome with grief, she is not swooning or held back, she is calmly meeting Jesus’ eye, calmly gazing at me. In the distance you can make out the entrance to a tomb and two men in white sitting before it. A foreshadowing of the resurrection. But Mary can’t see the tomb, at this moment she is probably not thinking about resurrection. Instead she is merely present. Once again, Here I am.

Virgin of all virgins blest!,

Listen to my fond request:

let me share thy grief divine;Let me, to my latest breath,

in my body bear the death

of that dying Son of thine.