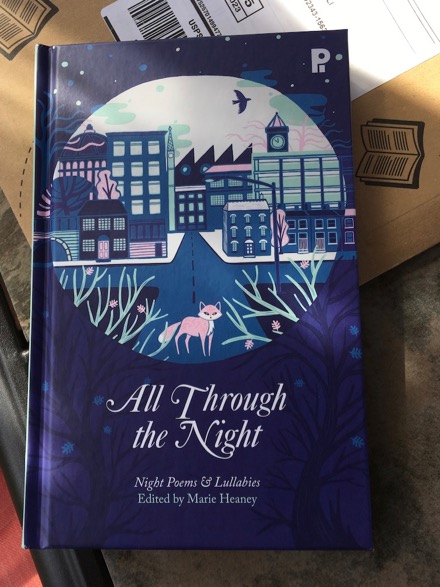

All Through the Night: Night Poems and Lullabies edited by Marie Heaney

When Dom had to go into the hospital for some tests, I found myself stranded in the hospital waiting room with the ubiquitous television’s relentless beating, with talk show blather and inane commercials. My phone was almost dead so I couldn’t waste time on social media. I was so grateful I’d brought my book of poetry with me. Each poem a little world, entire unto itself, a tiny refuge for the soul. Island hopping through an archipelago of verse, each one so different, needing to be inhabited. So many fantastical variations on the lullaby, so many different images of the night.

I stumbled upon this book while following Seamus Heaney rabbit trails. The interview with his wife Marie was lovely and I was quite intrigued that she’d edited an anthology of poetry and was especially intrigued by the theme of lullabies and night poems. When I mentioned the anthology on Facebook, my sweet mother decided to buy it for me.

When I opened the package and pulled out the book my very first impression was that this is a book that is lovely as a physical object, a well-made thing. The cover has a delightful texture, smooth but with a slightly raised texture for the design. The binding is solid and the kind that won’t easily break at the spine; the quality of the paper, the illustrations… it’s a book made to be read and reread and cherished and passed down.

Of course I wouldn’t want to judge a book by its cover. What really makes this anthology fantastic is the selection of poems.

A brief peek at some of my favorites:

Fair Rosa, a traditional Irish lullaby, is a retelling of the Sleeping Beauty story. The chorus is a repeated, “a long time ago.”

Fair Rosa was a lovely child… a long time ago… a wicked fairy cast a spell… a long time ago…

Simple repetition and a simple chorus, a very sketchy outline of the familiar tale, it’s charming and I could imagine myself singing it to my own baby, if I had one right now. It’s that kind of poem, I want to make up a tune and croon it to a sleepy child. I also appreciate the slight irony of the final verse: “Fair Rosa will not sleep no more, sleep no more, sleep no more…” How often the theme of the baby who just will not sleep comes up in lullabies, the words giving vent to the parent’s midnight frustration.

+ + +

The Sleepy Song by Josephine Dodge Daskam Bacon begins and ends with the fire burning red and low. It’s a poem that plays with the notion of counting sheep, though there is no actual counting. It’s voiced by the child who tells of “a queer little sleepy song” that her mother sings to her. The sheep tumble past dreamily, grey and white playing follow the leader and running over the hill… it’s much more hypnotic than actually counting sheep.

+ + +

Seoithín, Seo Hó/ Hushaby, Hush is one of several poems in Irish presented with a facing English translation. “Hushaby, hush, my child and my treasure, / my guileless jewel, my portion of life…” The singer prays for the child in the first stanza, but my favorite part of the lullaby is the second stanza in which the singer imagines the evil things outside, this is a not uncommon element in Irish lullabies:

“On the roof of the house there are bright fairies,

playing and sporting under the gentle rays of the spring moon;

here they come, to call my child out,

wishing to draw him into the fairy mound…Hushaby, hush, you’re not going with them.”

+ + +

Shane McGowan’s Lullaby of London has long been one of my favorite Pogues songs (I used to listen to it over and over again to fall asleep). Seen in this context, as one poem among many other lullabies, I notice how this beautiful urban lullaby very clearly echoes many of the traditional Irish lullabies in the first part of the collection. It contrasts the traditional corncrake’s cry with the night sounds of the city, but at the same time it echoes the traditional blessings that wish away ghosts and fairies and evil spirits and invoke angels and saints. It’s tender and lovely and rather wistful, seeing it here made my heart leap up.

“. . . Heard a long gone song

From days gone by

Blown in on the great North windThough there is no lonesome corncrake’s cry

Of sorrow and delight

You can hear the cars

And the shouts from bars

And the laughter and the fights. . .”

”

May the wind that blows from haunted graves

Never bring you misery

May the angels bright

Watch you tonight

And keep you while you sleep”

+ + +

Delia Murphy’s Connemara Cradle Song is sung by a mother whose husband is away fishing: “On the wings of the wind, o’er the dark rolling deep, / Angels are coming to watch o’er thy sleep, / . . . so list to the wind coming over the sea.”

She prays for the fishermen: may the fury of the winds be crossed, may the wind blow lightly, “may no one that’s dear to our island be lost.” And, having addressed her fears, she ends on a hopeful note:

“The Currachs are sailing way out in the blue,

Laden with herrin’ of silvery hue,

Silver the herrin’ and silver the sea,

And soon they’ll be silver for baby and me.”

I really like the way the final “baby and me” echoes the end of pat-a-cake, that nursery-rhyme feel.

+ + +

Derek Mahon’s villanelle, The Dawn Chorus, is haunting in much more cerebral way, invoking the kind of existential angst that creates a void when faith and dreams are gone and that haunts the early hours of the morning when wakefulness lingers so long that you hear the birds awaking. The two repeating verses are: “It is not sleep itself but dreams we miss” and “We yearn for that reality in this.” What is life without dreams? If we can no longer dream of heaven, of a better world, if we cannot create worlds of the imagination… we long for the reality of faith and of the supernatural, the transcendent…. the poem teeters on the brink of despair and yet somehow the wistful longing itself feels almost hopeful.

“If only we could achieve a synthesis

Of the archaic and the entirely new”

I love the grappling with intellectual dilemma here, contrasting with the natural sounds of the birds and with the dreamy symbolic imagery.

“But, wide awake, clear-eyed with cowardice,

The flaming seraphim we find untrue”

“Clutching the certainty that once we flew”

+ + +

Moya Cannon’s Night opens with a series of martial images: the narrator finds herself driving home at night “ambushed / by the river of stars” and then is “disarmed” and explains “I wasn’t ready / for the dreadful glamour of Orion”. The poem distills the way beauty shocks us. But the poem shifts from the martial images of the beginning to a playful vision in the final stanza, when she gets out of the car “rather than drive into a pitch-black ditch” (her risk of bodily harm from beauty’s ambush). Not enough that the poet be ambushed by beauty, she springs her own surprise on the reader when she leans against her car and stares

“at our windy untidy loft

where old people had flung up old junk

they’d thought might come in handy,

ploughs ladles, bears, lions, a clatter of heroes

a few heroines…”

Suddenly the sky with its constellations is an attic storeroom full of junk, careless tossed up, just in case it might be useful. Where the third and fourth stanzas evoke Orion as a personification of beauty and fierce power, in the final stanza the myths and legends are “old junk” and the ancient poets “old people”. And yet such is the power of Cannon’s imagery to ambush and delight the reader, that far from feeling resentment at her demythologizing, I am delighted at the turn and, like Venus in the final line, “almost within reach,” I find myself “completely unfazed by the frost”. For Cannon, cleverly realizing that for most of us the old myths have lost the sense of wonder and delight, breathes new life into them and helps me to remember the delight of my first love of tracing a new-found constellation picture in the stars.

+ + +

There are many classic poems included, too, which I won’t mention by name: by William Blake and Robert Lewis Stevenson, William Shakespeare, and Emily Dickinson…. There are old familiar favorites like Matthew Arnold’s Dover Beach, Keats’ Ode to a Nightingale, Tennyson’s Crossing the Bar, Dylan Thomas’ Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night… The collection is heavy on the Irish poems, but there are many other voices here as well: British, American, Australian, Scottish, German, Welsh…. The collection feels balanced, thoughtful; full of many moods, many voices.

One Amazon reviewer complained that this is not an anthology of lullabies to sing to children at bedtime as she’d anticipated. That is true, it is not really that. Though Sophie and I spent a pleasant while curled up together in the recliner, me reading poems to her and both of us sighing in appreciation. There are some dark poems here. There are some that deal with adult themes: sex, death, war. They might not all be suitable for a child browsing. Certainly they are not all lullabies and nursery rhymes. But I think that’s what I like about this volume. There are poems that grate a bit, that jar, that unsettle and disturb…. and it seems to me that an anthology of night poems that didn’t include that, might be a little unbalanced. As it is, I think this one is just about perfect.

You can see

a preview of the table of contents and first twenty pages here.

This sounds wonderful. Thanks for the recommendation!

You are most welcome. Yesterday my sister arrived and we spent a merry hour sitting around the dining room table with me reading some of my favorites to her while some of the children listened in. And she concurs that it really is a delightful collection.

This looks lovely, but I am afraid it would drive me mad wanting to know the melodies.

Of course, when I was a child, I sang my way through “Best Loved Poems of the American People,” so I supposed I could try that.

AMDG

I totally understand, and I’m not even a very musical person. Sometimes You Tube can help; but not always. I have made up the tunes to many a poem since becoming a mother. It sort of drives me a bit crazy because I know my tunes are “wrong” but my kids seem to like them, so there’s that.

And then, think about how often the Church uses the same tune for 5 or 6 different songs, or more than one melody for the same lyrics, so it’s a good tradition.

AMDG

A good point. I tend to learn one melody and then sing everything in the Liturgy of the Hours that fits the meter to that one tune. And then I sang lots of made-up lullabies to my kids to the tune of Frere Jacques.