On Friday I took the kids to our homeschooling group’s annual Lenten retreat. The theme of this year’s retreat was The Seven Sorrows of Mary. A young priest, Fr. Anthony Cusak, (himself a homeschool graduate) gave a meditation for the mothers that was just beautiful. As he spoke of the Flight into Egypt he referenced a painting at the MFA. I knew I needed to go look up the painting and also that I needed to go look up art to go with all the sorrows and to post them here with some of what I remember from his talk and some of my own thoughts and reflections. So here is the fourth of a planned series of seven posts: First: The Prophecy of Simeon, second: Flight into Egypt, third: The Loss of the Child Jesus in the Temple, fourth: Meeting Jesus on the Way of the Cross, fifth: The Crucifixion.

Joseph of Arimathea, a respected member of the council, who was also himself waiting expectantly for the kingdom of God, went boldly to Pilate and asked for the body of Jesus. Then Joseph bought a linen cloth, and taking down the body, wrapped it in the linen cloth, and laid it in a tomb that had been hewn out of the rock. He then rolled a stone against the door of the tomb. Mary Magdalene and Mary the mother of Joses saw where the body was laid.

Mark 15: 43, 46-47

Jesus’ passion is over. He is dead. He suffers no more. But Mary continues to suffer; another sword pierces her heart. They take his body from the cross and lay it in her arms and she holds her son one last time.

Does the Bible describe Mary holding Jesus, does it say she was there? Not in so many words. But it does tell us that she and Mary Magdalene saw where the body was laid. If she was there to see him die on the cross and she was there to see him put in the tomb, she surely would have helped to tend his body and wrap it. She surely would have caught her beloved son up in her arms one last time.

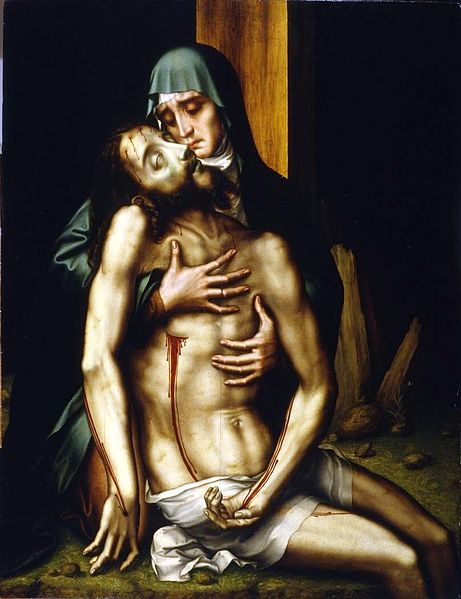

The pieta is a beloved subject in art and it’s hard to choose just a handful of paintings to focus my meditation; but here are a few that caught my eye.

Luis de Morales’ Pieta shows Mary seated at the foot of the cross, holding the very obviously deceased Jesus. The background is black, there are no other people, our attention is focused on Mary and Jesus, on Mary’s singular solitude. He sits upright in her lap, his face is close to hers, the pose is reminiscent of a Madonna and Child icon in which the Child presses his face tenderly against the Virgin’s cheek. But this grown child is limp; his face is slack, eyes closed, mouth open, hands hanging limp; and face, arms, side are streaked with blood. Mary quite obviously has to work to hold him upright, to keep him from slumping over, the position of her hands seems awkward. Mary’s face is tender and restrained, a deep, quiet grief as she casts her eyes down to look at the face that is so near to hers, she is caught up in her pondering, oblivious to the world beyond her dead son.

The dark background, Mary’s dark clothes, and the stark lighting make this a somber, brooding picture. The focus is really on Mary and her grief and on the corporality of the dead Jesus. The drama is all internal, the picture feels still, contemplative, not dynamic or emotive.

The composition of Bellini’s picture is similar but much more dynamic and active: Mary hold Jesus upright and presses her face near to his; but the composition is brighter, more colorful, and is set in a pastoral landscape with a city in the distant background. Nevertheless Mary’s veil and John’s tunic are both black, signifying mourning. Bellini doesn’t include the cross and does include a distressed looking St John who helps Mary to hold Jesus up but turns away his face. Bellini’s Mary looks older, careworn, grief-striken. She has been through a long ordeal and her face shows it. She rests her chin on Jesus’ shoulder, looking closely into his closed eyes. Her lips are barely parted, as if she is whispering to him. There’s almost an urgency is her features, as if she’s admonishing him. Or is she singing him a lullaby? It feels like something is happening there. Mary hold his hand in hers, both a tender gesture of a mother cradling her son, and, combined with the hand that almost sticks out of the foreground of the picture, a gesture for the sake of the audience: Behold his wounds. Calling to mind doubting Thomas, perhaps? Or maybe: “By his wounds you are healed.” Jesus’s face is much more serene in this painting, as if death has been a release from agony. As if, his mission having been accomplished, now he may rest.

Mary’s closeness to Jesus, the way her chin exactly fits in the hollow between his face and shoulder, the way her arm’s position mirrors his, speaks of the essential unity of the two. His mission is her mission, his suffering is her suffering. And his death is the greatest sorrow, the greatest pain, of her life.

Another pair of pictures by Tissot. The first one here shows Mary, seated on the ground at the foot of the cross, holding the body of her son. Tissot shows Golgatha as a realistic Palestinian landscape, rocky landscape and dark, brooding sky. Golgatha is a busy place on this Friday afternoon. Besides Mary there are more than a dozen women come to mourn and to prepare Jesus’ body for burial. Some men come too, carrying jars of oil to anoint him. In the background the thieves are also being taken down.

The action occurs not in the foreground as in Bellini’s painting, but in the remote middle. We are an audience to the drama, but hardly participants in it. This painting intends to tell a story more than to convey a truth or an emotion. But Tissot’s story telling is superb; he brings the time and place to life and he is as true as he can be to the people and events of a particular moment in history. Nor is he insensitive to nuance and the spiritual dimension of his subject matter. Rather, he invites us to enter the scene, to live the moment, to be transported to a different time and place.

Mary lifts Jesus onto her lap, cradling his head in her hands, pressing her face against his, the crown of thorns removed and placed beside him on the edge of the burial cloth. Another woman holds his outstretched hand and presses it to her face, kissing it. Two other woman (is one of them Mary Magdalene?) throw themselves across his feet, their jars and cloths abandoned on the ground nearby. The other women behind them seem to be weeping and wailing, their hands raised to their faces or clasped together in gestures of grief.

James Tissot: The Holy Virgin Kisses the Face of Jesus

This second Tissot scene takes place not too long after the first. Now Jesus’s body has been anointed and wrapped and they are about to put on the final layer that will cover his face. Mary bends down to kiss his face for the final time. Most of the women around Jesus kneel, there is a sense of liturgy, of worship, as they all gather round. One of the edges of the shroud is being held by a Roman soldier, is it the centurion Longinus who pierced Jesus’ side with his spear and came to believe in Jesus’ divinity.

The liturgical postures of this image speak to me most of the beginning of a new stage in Mary’s life. This is the end of her earthly motherhood as she hands her child over to be taken to his tomb. This is the final kiss, the farewell to that particular kind of relationship that she has enjoyed up to now. Now begins the new sacramental and liturgical life of the Church. Although Mary remains close to her Son, none closer, she must still feel a physical separation after the ascension, when his bodily self is taken up into heaven. Surely she must miss that face, that voice, the way his hair moved, the way he walked and the way she knew his favorite food

He is dead and nothing will ever be the same again. Mary believes in the resurrection and yet she still weeps and mourns her loss. Even Jesus wept when his friend Lazarus died and he was about to raise Lazarus from the dead. So too his mother weeps and her grief does not negate the promise of the resurrection. Rather she like the Church she represents, is caught in the in-between space of sorrow for sin and pain and the effects of sin and joy at the prospect of heaven. And the sorrowful Mother is an icon of the Church Suffering.

Mary waits in hope, longing for the glory of the day of resurrection just as the watchman longs for the light of dawn when his long, dark vigil will be over. She knows that her personal vigil is as nothing compared to all the time that Israel has been waiting for this moment, for the moment of the promise, the moment of the covenant, the moment of the Messiah, the moment of redemption.

Out of the depths I cry to you, O Lord,

Lord, hear my voice!

O let your ears be attentive

to the voice of my pleading.If you, O Lord, should mark our guilt,

Lord, who would survive?

But with you is found forgiveness:

for this we revere you.My soul is waiting for the Lord,

I count on his word.

My soul is longing for the Lord

more than watchman for daybreak.

Let the watchman count on daybreak

and Israel on the Lord.Because with the Lord there is mercy

and fullness of redemption,

Israel indeed he will redeem

from all its iniquity.Psalm 130

[…] Two weeks ago I took the kids to our homeschooling group’s annual Lenten retreat. The theme of this year’s retreat was The Seven Sorrows of Mary. A young priest, Fr. Anthony Cusak, (himself a homeschool graduate) gave a meditation for the mothers that was just beautiful. As he spoke of the Flight into Egypt he referenced a painting at the MFA. I knew I needed to go look up the painting and also that I needed to go look up art to go with all the sorrows and to post them here with some of what I remember from his talk and some of my own thoughts and reflections. So here is the fourth of a planned series of seven posts: First: The Prophecy of Simeon, second: Flight into Egypt, third: The Loss of the Child Jesus in the Temple, fourth: Meeting Jesus on the Way of the Cross, fifth: The Crucifixion, sixth: The Descent from the Cross. […]