Autonomy Is the Child’s Secret Dream: Free-Range Books, Competence, and Constraint

For some time I’ve been aware of this common theme running through so many of our just-for-fun read-aloud books. So many of them could be described in the same general way: a bunch of siblings, who spend most of their free time with each other, making their own fun, being independent of adult supervision for great amounts of time, having adventures and solving problems, who are resourceful and brave and who make mistakes and learn from them.

These are the sorts of books I seek out. When I’m surveying my bookshelves for our next read aloud this is the kind of book that will most call to me. We read plenty of other kinds of books too, but we usually have at least one book going that would generally fit this description.

This week several different conversations made me think more deliberately about this sort of book, and I’m trying to tease out various ideas but I’m not exactly sure where I’m going with this, so please bear with me.

Free Range Books

First, Jamie of Light and Momentary has been writing about raising children to be independent and resourceful and resilient (It starts with sidewalks and It’s more than sidewalks. Among other things in this wonderful piece, she posted a link to a blog post about picture books that promote Free Range kids: Help! ‘Free-Range Kid’ Epidemic Is Spreading to Picture Books. It mentions quite a few of our favorites: little Peter wandering the urban sidewalks in The Snowy Day, Sal picking her blueberries, Lisa going by herself to buy Corduroy from the department store, Harold walking away in the moonlight with his purple crayon. Oooh. I like this idea of identifying free-range themes in picture books. Let’s include Dahlia, Adele and Simon, Roxaboxen,

Then, Jamie asked her readers to recommend more books for teaching children about competence.

Whatever your neighbors are doing with their kids, you can define normal within your own house. I suggest doing this through classic children’s books, which describe a world in which young kids routinely went places on their own. . . . Here is the image that springs to mind: reading about how kids occupied themselves in the 1940s and 50s and 60s feels like blinking in the sunlight when you walk out of a matinee — both uncomfortable and refreshing. We have all been immersed in a constrained and artificial version of kids’ abilities. It’s time to exit that theater.

In the comments to Jamie’s post Melissa Wiley responded with her own delightful list of books, several of which would have been on my list had she not got to them first, and I added my own suggestions.

Anne of Green Gables has kids who wander through the woods, walk on ridgepoles, start clubs, save lives (Minnie Mae and the croup). All of L. M. Montgomery’s kids are pretty free range.

Hilda van Stockum’s Bantry Bay and Mitchells series. The Bantry Bay kids wander all over Ireland, especially in Francie on the Run. The Mitchells go on subway adventures and collect scrap and solve problems when they break expensive statues and help to stop a forest fire.

Oh and the Melendys! Free range kids in New York City in The Saturdays and in the country in the other books.

When You Reach Me. Miranda wanders about New York, too.

From the Mixed up Files of Mrs Basil R Frankweiler.

Little Women, Chronicles of Narnia, the Little House books. Miss Happiness and Miss Flower. The Kitchen Madonna. Really all of Rumer Godden’s kids’ books. Oh and don’t forget Edgar Eager: Half Magic! Sun Slower Sun Faster. Noel Streatfield’s Shoes books.

I mused: Actually, pretty much all of my read aloud list of novels that I haven’t chosen because they tied in with our history studies have been chosen with the sort of semi-conscious criteria that they are a sort of Free Range Literature. I deliberately choose books which portray competent children occupying themselves in interesting ways that are not dependent on adults. Also, a bonus if the kids are from larger families and spend their free time playing with their siblings.

I’m sure I could come up with more and more books. As Jamie says, almost all books about kids from the 40s and 50s and 60s (and before) show them as independent and competent. But then something shifted and, as another commenter notes, “Isn’t it funny that many more recent books about children-on-their-own have to *do* something to the adults to explain why the kids are on their own? Orphans in danger (Mysterious Benedict Society), etc. But Swallows, Laura, etc. could have parents AND still be free to DO much.”

That’s a really interesting observation. There are many more recent books that show child protagonists doing amazing competent things. But most of them are doing these things because the adults have failed them, are absent or incompetent. Whereas in the older books the adults often just trust the kids to be competent and responsible. (And I am led to wonder whether the hyper-incompetence of the adults in Harry Potter and the extreme dangers faced by the child protagonist and his friends might not be a sort of extreme reaction to contemporary constraints on children, a fantastically rebellious flight of fancy in which children are able to overcome the most extreme challenges and to save the adults all on their own.) Strangely, another literary friend was asking for recommendations of stories in which children solve problems for adults that the adults cannot solve for themselves. She thought that Telemachos was a type of that story, but couldn’t find another example until the modern era. And I wonder is this autonomy or something more? Doesn’t the child as savior trope seem to be not merely about competence and independence but about a sort of wish fulfillment? I’ll have to think on this some more.

Unsupervised Children

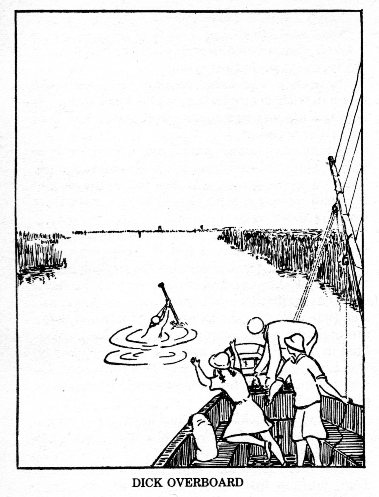

Nonetheless, thinking about that model of older books in which the adults turn their backs and practice masterly inactivity, allowing the children space to learn responsibility, brings me to the books that really should have been at the top of the list, but Melissa Wiley mentioned them first and anyway I was saving the best for the last: Swallows and Amazons. And here’s where I pick up another conversational thread. Sally Thomas wrote a really good, thoughtful piece (but that’s redundant because Sally’s writing is always good and thoughtful) about Swallows and Amazons, that fits perfectly into this discussion of independence and competence. Not Duffers, Won’t Drown.

These stories are all about unsupervised children,” my oldest daughter observed years ago, when we were reading Arthur Ransome’s Swallows and Amazons books aloud, one after another, books in which—to offer a rough collective plot summary—some children mess about in boats. “How,” my daughter asked in marveling tones, “did these children get to be so unsupervised?” Autonomy is, after all, the child’s secret dream. To go out alone and live, even if all you do is swim, fish, cook regular meals, and go to bed when it gets dark, is a vision beyond the reach of the average child today.

The very simplicity of this dream—absent the flamboyant magic, vampires, zombies, or killing so common in contemporary children’s fiction, absent the issue-driven personal or family drama with which those books tend to be laden—is the deep magic of the Swallows and Amazons books. The need of children to be world makers is the truth these stories tell.

I love Sally’s insight that children need to be world makers. (Does that hold true for all of these free-range stories? I wonder.)

One of the interesting features of the Swallows and Amazons series is that there are two books that take place wholly within the children’s imagined world. In Peter Duck and Missee Lee they load the Swallow and Amazon onto a schooner named the Wild Cat and sail off to the far reaches of the map. In Peter Duck they search for buried treasure in the Caribbean. In Missee Lee they encounter pirates in the China Seas. Their imaginary world is fully realized complete with villains and storms and calamities. In these stories the responsible adult is Nancy and Peggy’s Uncle Jim, aka Captain Flint, who is himself rather childish in his ability to enter into the children’s play and who disappears for a good part of the narrative. And that absence of adults seems to be critical to the shape of the stories. As Sally Thomas continues,

At the same time, however, this universe, safe and ordinary, extends to its children a fund of imaginative potential. For these characters whose mother is willing to turn her back on them just a little, a lake becomes an ocean, its far shores another country, its collection of villagers, farmers, and charcoal burners natives to be approached cannily by intrepid explorers whose self-imposed summer’s work is to map these unknown lands. After all, they have to do something with their time, never mind that according to the literal-minded adult world what they do is essentially nothing.

It’s hard to imagine publishing, now, a book about ordinary, everyday children doing what normal, everyday children do, because what children do in our world is not nothing. Children don’t do nothing any more, even on their holidays. They take lessons. They play sports. They go to camps.

Today the best known child hero is arguably Harry Potter, whose universe is anything but safe and ordinary. Is the rise of Harry Potter and his dangerously fantastical world somehow necessitated by the ultra-safe, hyper-organized reality we’ve constructed for children where they have no room for doing nothing?

I’ve been asking myself: Why do I keep choosing books like this? And well, isn’t it mainly because they’re ripping good tales, full of adventure and fun, and the kids enjoy them, and I enjoy them? Reading good books together is a major part of our family culture and I want there to be some books we are all looking forward to, longing to find out what happens next. All of our school books are interesting, but not all of them have everyone begging for more, sad when we miss a day, crying, “Please can we have another chapter?” at the end of each day’s reading. I don’t want to lose sight that the main reason we read is for delight and not for themes or ideas. But once we’ve settled that, I have to acknowledge that there’s a pattern to my choices and perhaps an ulterior motivation.

And yes, it is partly, as Jamie suggests, because I feel my parenting is constrained: I’m not able to give my kids the freedoms I wish I could. They can’t go run about in the woods, bike to the store or library, roam the neighborhood at will. They certainly can’t sail about on lakes, build camp fires, and camp alone on an island. So there’s a certain freedom of the spirit, a vision of competence and independence that I want my children to have if only as an imaginary space they might inhabit, a template to be filled in at a later date. A promise. A downpayment I hope to be able to reimburse in full someday when society’s expectations about what sorts of independence are appropriate for their ages aren’t quite so far from mine. And maybe a bit of a goad to myself, a prompt to turn my back a little more often, to allow plenty of time for doing nothing, and well, maybe to look up whether it might be practical at some point to give the kids sailing lessons?

Love this post! Love love love!

I’m glad you approve. I’d never have written it if it weren’t for you.

Yet what is now a secret dream used to be a normal childhood for many. I’m still haunted by an old stock photo of children someone shared on Twitter many months ago. It was a simple image of about a dozen children, ranging in age from Bella to Ben, sitting among some trees. The user pointed out that there wasn’t a single adult to be seen, and described the subjects as children who were allowed to have their own world.

I wonder if Bella’s zeroing in on the lack of supervision in books comes from a deep intuition that she and her very young peers are being denied an essential part of childhood. We really live in a culture of surveillance these days!

My own favorite autonomous children from literature are Almanzo Wilder and his siblings in Farmer Boy. I was gobsmacked by their parents’ leaving them at home for a few days, in order to visit relatives. Today, those hardy children would either be bundled along or have to endure the indignity of a baby-sitter. During those days of freedom, the Wilder siblings didn’t always make the best decisions . . . but neither did they blow the house up!

I’m also reading a German translation of The Garden of the Gods by the naturalist Gerald Durrell. It’s about his free-range childhood on the Greek island of Korfu, back in the 1940s. The book came out in the 1970s, and in the forward he already expresses regret that fewer and fewer “modern” children will never get to grow up as he did.

Ah to be clear, the daughter who noticed the lack of supervision was Sally Thomas’ daughter, not Bella. But yes, I think most kids are denied that kind of freedom to be unsupervised. I do try to give my kids large amounts of unstructured time and to let them have a pretty long “leash” when we go out, to wander out of my direct line of sight, but I’m always having to balance the amount of autonomy that makes me comfortable with other people’s perceptions of risk. It’s so frustrating.

I do love those housekeeping scenes in Farmer Boy so very much. And yes, it’s not like they don’t abuse their freedom, but in general even the rules they break are the minor ones and they fix everything up and the parents are none the wiser. And they learn from their mistakes! And I was just thinking today how much I wish I could even leave Bella home alone for an hour or so, but really I don’t think I can. Not yet.

Oh I love Gerald Durrell. We read My Family and Other Animals, which is also about his childhood in Corfu. I should seek out Garden of the Gods, his writing is fabulous. We also have a picture book by him called The Fantastic Flying Journey, about kids who circumnavigate the globe in a hot air balloon and talk with animals along the way. Kind of Dr Doolittle meets Around the World in 90 Days. It’s one of Bella’s favorite books.