Halfway through April and I’m finally getting to write up some thoughts on March’s reading. In this post I’ve only included books I’ve finished. There were quite a few other books that I picked up and put down and made no headway on. I have nothing to say about them at this time, so I’m ignoring them for now.

1. A Candle for St. Jude by Rumer Godden

St Jude is the patron of hopeless causes. The Holbein ballet company certainly seems a hopeless cause. Everything is going wrong. An interesting look at the inside of the ballet world. Not as much one of my favorites among Godden’s works because it seems very unfocused. Can’t quite decide which story to tell and flits from one to another. But it’s the kind of story that will stick with me and that I’ll want to re-read.

2. Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality, an online fanfic by Eliezer Yudkowsky

Some of my friends kept mentioning this book on Facebook. I’m really not at all interested in reading fanfic, but my curiosity finally got the better of me. I was at first drawn in by the concept: what if Harry had been raised by a loving aunt and uncle? In this alternate reality Lily Evans cast a spell on her sister Petunia that made Petunia beautiful. Then Petunia married a scientist and they adopted Harry and raised him as a nerd. Next, I enjoyed the way the author addresses the many inconsistencies in the original HP novels. The critique of Quiddich, for example, was spot on:

“So let me get this straight,” Harry said as it seemed that Ron’s explanation (with associated hand gestures) was winding down. “Catching the Snitch is worth one hundred and fifty points? ”

“Yeah -”

“How many ten-point goals does one side usually score not counting the Snitch?”

“Um, maybe fifteen or twenty in professional games -”

“That’s just wrong. That violates every possible rule of game design. Look, the rest of this game sounds like it might make sense, sort of, for a sport I mean, but you’re basically saying that catching the Snitch overwhelms almost any ordinary point spread. The two Seekers are up there flying around looking for the Snitch and usually not interacting with anyone else, spotting the Snitch first is going to be mostly luck -”

“It’s not luck!” protested Ron. “You’ve got to keep your eyes moving in the right pattern -”

“That’s not interactive, there’s no back-and-forth with the other player and how much fun is it to watch someone incredibly good at moving their eyes? And then whichever Seeker gets lucky swoops in and grabs the Snitch and makes everyone else’s work moot. It’s like someone took a real game and grafted on this pointless extra position so that you could be the Most Important Player without needing to really get involved or learn the rest of it. Who was the first Seeker, the King’s idiot son who wanted to play Quidditch but couldn’t understand the rules?” Actually, now that Harry thought about it, that seemed like a surprisingly good hypothesis. Put him on a broomstick and tell him to catch the shiny thing…

Ron’s face pulled into a scowl. “If you don’t like Quidditch, you don’t have to make fun of it!”

“If you can’t criticise, you can’t optimise. I’m suggesting how to improve the game. And it’s very simple. Get rid of the Snitch.”

Even though at times the emphasis on rationality was a little annoying, especially the materialist rejection of the idea of an afterlife, I didn’t feel that the author excluded the possibility that his Harry is wrong. I mean it seems pretty clear the author believes as Harry does, but so do plenty of other people. Nonetheless Dumbledore and other characters in the novel do believe in an afterlife.

The last enemy to be defeated is death. The character of Harry James Potter-Evans-Verres shares the modernist materialist secularist view that death is the ultimate enemy. Death not sin. So it’s wrong as much as it is right. Death is surely an enemy and yet Harry can never be the messiah who will overcome death. But the character is limited by reality and the shortcomings of his worldview are apparent. And yet I think the critique of Rowling’s world is a good one. Especially the critique of a society that accepts Azkaban and Dementors as a necessary evil.

I read this novel obsessively for the better part of two weeks. To be honest, it really ate into my Lenten discipline. I never could settle on a spiritual reading that I liked and so I drifted off to reading this fiction that I couldn’t put down.

It’s a book I feel I still want to process. I’d love to find people to chat about it with.

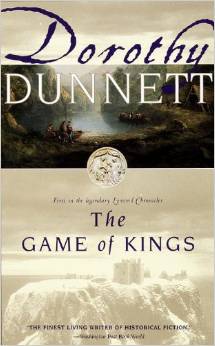

3. The Game of Kings by Dorothy Dunnett

The first in the Lymond Chronicles, my favorite historical fiction. Dunnett is a master story teller and Francis Crawford of Lymond is a brilliant creation, one of my favorite literary figures of all time.

I first read the Lymond Chronicles when I was home sick recuperating from a job so stressful that I decided to just call and quit because I couldn’t face going back to work. Was my decision fueled in part by my inability to put down the books? Perhaps. I certainly didn’t do anything to look for a job until I’d finished the series. Just lay in bed reading all day and late into the night with breaks for meals and hanging out with the roommates.

In this first novel, set during the childhood of Mary, Queen of Scots, when England is ruled by the boy-king Edward, the son of Henry VIII, Scotland is at war with England because the English want to seize the Scottish queen and forcibly marry her off to their king and thus unite the two realms. The Scots, however, aren’t thrilled with the idea. At least some of them aren’t. Some of them are quite willing to play both sides and some are actively working for the English. The question is, what is the ultimate loyalty of our hero, Francis Crawford, the Master of Culter, the second son of a minor Scots noble? He’s been accused of treason against the Scottish crown. He’s also accused of terrible war crimes. Is he a hero or an anti-hero? It’s easy to spend most of the novel on the fence about that question.

One of the things I love best about these books is that our omniscient narrator almost never gives us a peek into Lymond’s head. We see him instead through the kaleidoscope view of all the people around him, whose understanding of him might be limited by personal history, by strong emotions, by incomplete information, and perhaps by not being quite as smart as Lymond is.

For Lymond is brilliant. A genius. A true Renaissance man, in both senses of the word. First, he is an accomplished musician, a brilliant swordsman, a charismatic leader of men, a polyglot. Very well educated, he constantly quotes poetry and literature in many different tongues. Dunnett provides no translation or glosses for these snippets. (Though there is a Dorothy Dunnett Companion which will provide those if you want to invest in it.) Don’t worry, he’s far from flawless and he’s not insufferably insipid as this list might imply. Second, Lymond is also a political mover and shaker in the world of Renaissance Europe. He might have the power to influence the fate of more than one nation. Will he use that power for good or ill? If you want to immerse yourself in Renaissance politics and culture, these books are delightful. This is a delightful romp through history, but Dunnett is not a storyteller who coddles her reader. Important details are often hidden in plain view. On almost every page I have a nagging feeling I’m missing an important subtext, even on this my third re-read. These aren’t easy books, but they are so very, very worth the effort.

These are the kind of books I want to go back and re-read immediately when I finish the series because now I finally see how it all fits together. Or perhaps I could see if I re-read them because I think I missed a few things the first go round. Or the second. But they’re pretty massive, so that re-read is also a daunting task. I’ve been planning this re-read for several years, waiting until I didn’t have a nursing infant waking me up at all hours of the night.

I feel like the grandfather in The Princess Bride. This book has everything: archery, fencing, disguises, amnesia, drunken carousing, wild midnight border skirmishes, cattle raids, fair maidens in distress, brilliant double and triple crosses, true love, blackmail, all-night card games where death is on the line.

Lymond Chronicles are in my TBR. It won’t surprise you, I’m sure, but Guy Gavriel Kay was inspired by Dunnett. It heard it on NPR over Christmas .

Oh yes! I read about his first meeting with her some years ago on the official GGK fan page: http://www.brightweavings.com/ggkswords/dunnett.htm

I love the way he just showed up on her doorstep. And how she was so very gracious. Such a delightful story about two of my favorite authors.

I love this NPR tribute, too, thanks for the link. It’s true that being a Dunnett fan seems mean you’re a member of an even more exclusive club than the Kay fan club. She doesn’t seem to be widely known and then you’re surprised at who does know and love her. She’s definitely a writer’s writer.

The book about Harry Potter sounds very interesting! But “the last enemy to be defeated is death” is from Scripture. I’ve always felt like HP was a good portrait of a literary Christ figure, despite other flaws in the story.

Well, the author takes the scriptural reference and interprets it in a materialist sense. This Harry Potter explicitly rages against the idea of life after death. His mission is to destroy death precisely because he sees it as the end. And yet the book offers an interesting opportunity to really think on why death is the last enemy and what it means for Christ to defeat it.

I’m still pondering this novel’s take on Harry as a Christ figure. He’s deeply flawed in a different way than Rowling’s character. He consciously sets himself up as a secular Messiah, out to save the world from Death. It’s not at all a Christian story on the literal level. And yet it’s an interesting treatment of the theme. And I think the story may ultimately point toward why the cross is necessary. In some ways, it’s a more complex approach to the problem of suffering than Rowling’s is. Rowling’s Harry is a Christ figure because of external symbolism and yet he often lacks empathy and fails to love his enemies. Eliezer Yudkowsky’s Harry is capable of deep empathy and does love his enemies even while he makes very disturbing pragmatic decisions about the value of individual lives.

Oh and here’s a great interview: http://www.fantasy-magazine.com/non-fiction/articles/a-conversation-with-guy-gavriel-kay/

“GGK: Dorothy was unmatched at the revelation of character through action, as opposed to stopping a narrative to ‘do’ the character-stuff, which so many writers (and that includes the serious ones) end up doing. She was also a role model in terms of the value, the necessity of doing your homework, your research. She exemplified as a writer the notion that entertaining stories are not remotely inconsistent with complex thought and character. All of these elements in her work (and more) will be noted by a wide variety of writers, and that extends far beyond and outside fantasy.”

Not Guy Gavriel Kay related, except that she links to his obit, but I like this reflection about Dunnett: http://www.ibooknet.co.uk/archive/news_june04.htm#Feature

Her first impression of Game of Kings makes me smile:

“It was 1992 and I was searching the shelves in my local UBS, chatting with the owner as one does. Nothing leapt into my hands crying “Read me!” so I asked for a recommendation. “Many people like Dorothy Dunnett”, he said, and handed me a slightly tatty paperback with a really naff historical-romance cover. Now, I love historical fiction but not with ’70’s bodice-ripper cover art. Dubiously I took it home and managed to get through one chapter. Set in 16th Century Scotland, the language was superb but it required work and attention to read, and frankly, the hero didn’t appeal to me at all. He was an arrogant poser who disrupted Edinburgh, set fire to his mother’s house and stabbed her best friend in the arm in the first 50 pages: a blond rapier who quoted poetry in 5 languages and was nasty to everyone. I took it back, and with the trade credit bought something eminently forgettable.”

And this about trying to get people to read Dunnett:

“During the interim I bored everyone to the point of death about this extraordinary writer: her pellucid prose, her intricate characters, the multitude of real historical figures and meticulous research…the puzzles… the settings. No-one I met had even heard of her. My English teacher colleagues at the secondary schools I taught in, all gave back my loaners saying “too much work”. I was desperate to talk to someone, anyone, who had read Dorothy Dunnett.”

“DD’s books are not easy reads, however. They require attention and thought. They are filled with false trails and really need to be read more than once. When I met Dorothy for the last time in Philadelphia I told her that I had still to read GEMINI because I didn’t want the journey to end. “Read it,” she said, “And then you can go back to the first book and read them again, this time looking for the clues.” She died in 2001. And I still haven’t read GEMINI.”

[…] hope I’ve pretty well established that I love Dorothy Dunnett’s Lymond Chronicles, my favorite historical fiction. But I confess that every […]